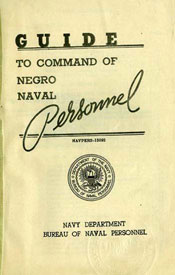

In recognition of the challenges in dealing with Negroes, the US Navy developed a pamphlet titled Guide To Command of Negro Naval Personnel (NAVPERS – 15092) in 1945.

The Guide notes the following:

The mission of the Naval Establishment is the protection of our country, its possessions and its interests. It includes neither social reform nor support of the personal social preferences of its personnel. In the accomplishment of this mission it is mandatory that the training and ability of all Naval personnel be utilized to the fullest.

It must be recognized that problems of race relations do exist and that they must be taken into account in plans for the prosecution of the war. In the Naval Establishment they should be viewed however solely as matters of efficient personnel utilization.

In general, the same methods of discipline, training and leadership that have long proven successful in the Naval Establishment will be found to apply to the Negro enlisted man. However, the effective administration and use of Negro personnel does call for special knowledge and techniques in some instances.

This is the result of the fact that Negroes as a group have had a history different from that of the majority of Naval personnel. Their educational opportunities have been restricted; the percentage of skilled workers is smaller; and participation in the life of the nation has been limited.

It is the purpose of this pamphlet to point out group differences in background and experience of significance to the officer with Negroes in his command, and to suggest approaches which may be of aid to him in the performance of his duties. The success or failure of each Commanding Officer in the administration of Negroes under him will be determined largely by the spirit in which he approaches the problem and the degree of attention given to it.

The Guide addresses potential problem areas such as “Symbols That Irritate,” “Even Compliments may be Misunderstood,” “Racial Separation,” “Transportation,” “Public Relations,” “The Negro Press,” “Rumors” and “Control of Venereal Disease.”

The title is outdated, and so is much of the Guide’s content. However, I found this to be a fascinating read for its frank and comprehensive treatment of the subject of dealing with African Americans in the military, and the window it provides into the mindset that whites in the military had toward blacks in the 1940s. It’s well worth your time to take a look.

White Southerners also had to adhere to the South’s code of behavior, or suffer consequences. This is illustrated in a true story from the book

White Southerners also had to adhere to the South’s code of behavior, or suffer consequences. This is illustrated in a true story from the book

That’s not something they teach in the schools. But our history lessons might look different in the future, if more people read the book Slave Nation: How Slavery United The Colonies And Sparked The American Revolution, by Alfred and Ruth Blumrosen. (The book cover is to the left.)

That’s not something they teach in the schools. But our history lessons might look different in the future, if more people read the book Slave Nation: How Slavery United The Colonies And Sparked The American Revolution, by Alfred and Ruth Blumrosen. (The book cover is to the left.)